Resident Experiences

Don’s Story

Marjorie lived at home with her husband Don who was of 87 years. He was an artist who attended weekly watercolour sessions with a local community gallery. She had advanced dementia and attended with him. However, Marjorie never participated and just sat on the edges of the group watching. She was non-verbal.

Don struggled to connect with her and motivate her to do things she used to love doing.

After a few weeks of the Drawing Memories Program, Don came to me with tears in his eyes. He told me how his non-responsive wife sat at the table with him in the watercolour class the previous week, and made art.

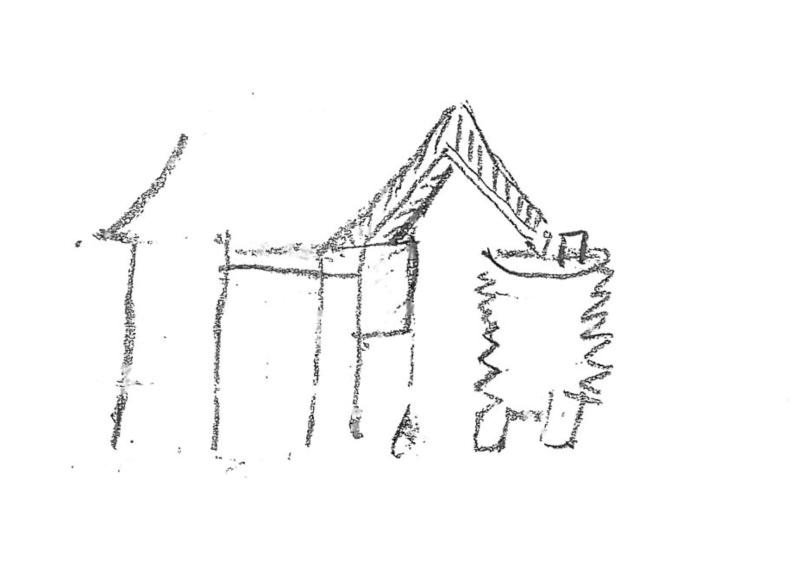

Totally unrelated to the class, she drew a tiny scene of a house and water tank. Don explained that it was a memory of their previous home in the country.

He was overjoyed and attributed her breakthrough to her participation in the Drawing Memories Program. Shared memories, re-connection with loved ones. That’s what art can do for people. It’s only natural.

Joan’s Story

Joan was diagnosed with dementia a few years prior to my meeting her but now her symptoms were advancing rapidly. When she was introduced to me, I was enrapt in her smile that shone from her eyes and radiated from her cheeks.

But Joan couldn’t communicate verbally.

The group I was facilitating was anxious to begin making art, but Joan just sat there with her beautiful smile, and seemingly to enjoy the company and buzzing atmosphere, but not interacting or comprehending in any way. Was her smile a cover-up for the confusion she faced every day?

She sat looking at the blank page with her hand hovering above it.

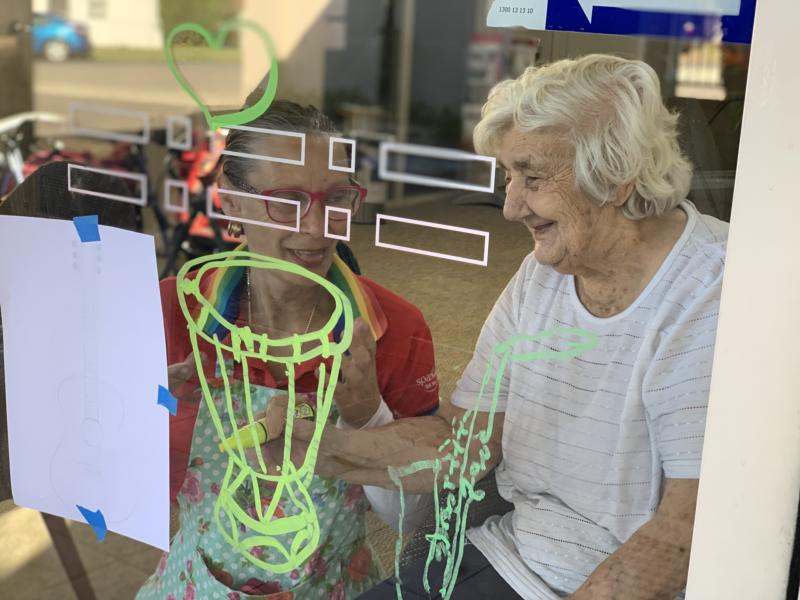

I knew the activity was a challenge and I knew the challenges of people with dementia to make sense of a blank piece of paper. I sat down and covered her hand that held a red crayon. When her trembling slowed, I showed her a colourful stripe I drew on my piece of paper.

I suggested she follow my movement.

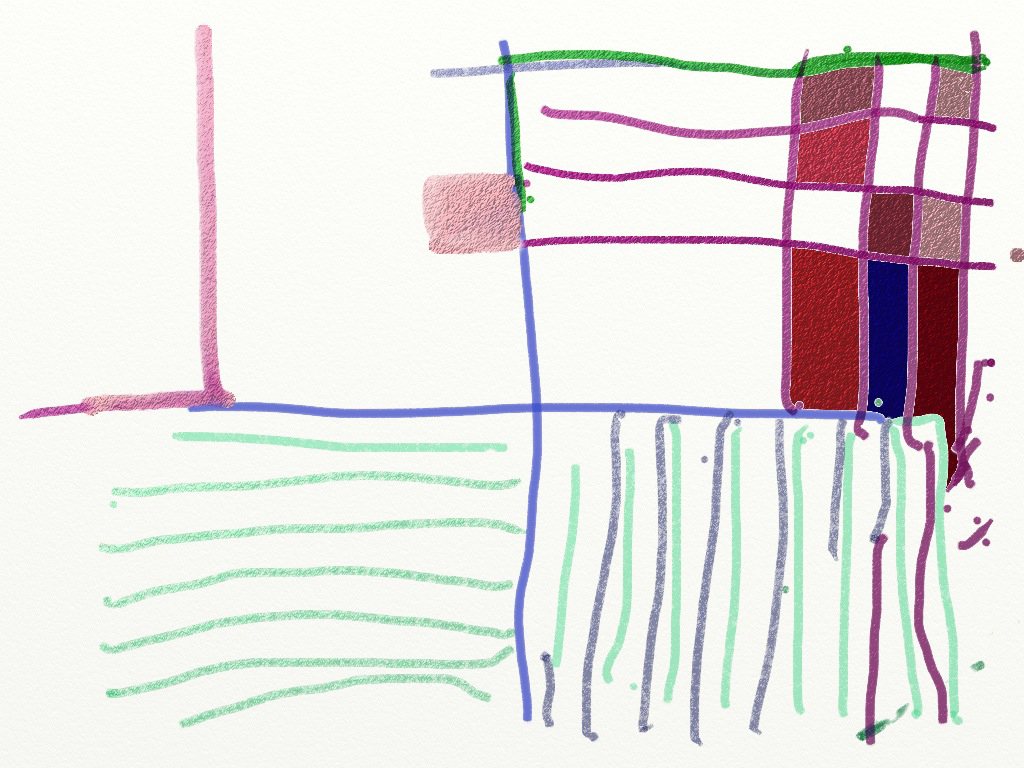

And she did. Repeatedly. Joan proceeded to choose her own colours and continued in her repetitive style until her page was filled with a delightful abstract drawing. No questions, no conversation, just the two of us together making marks.

So what is remarkable about this?

Joan showed a breakthrough in independent thinking – making choices in colours and shapes and lines.

Her agitation disappeared.

We connected in a non-verbal way. It was art for art’s sake, it was art for health’s sake. It was engagement and fulfilment in that moment.

Your Story

You should be planning leisure and lifestyle activities, but staff numbers are down, and you’re called to attend to the physical needs of your residents.

Organisational demands and clinical evaluations are taking up more and more time. You’re spending less quality time with the people you care for.

All you want to do is get on with what you’re good at – care and compassion for your elders’ emotional needs.

You should be off – you’ve done 7 days. The assessors are coming tomorrow and there’s high energy and low morale settling in.

Here you are doing the rounds, not sure if you’re counting pills, time or the repetitive clickety clack of the trolley wheels.

You need to draw a line somewhere between work and sanity.

Imagine…

Amongst the noise and clamour of the corridor you hear the faint strains of birdsong and Beethoven flowing through your routine. A gentle waft of lemongrass and eucalypt reaches your nostrils and just as you feel a sense of being on a bushwalk, you’re stopped by the scene before you.

There’s Stan, a retired electrician who lost his spark since his wife died. He doesn’t like art – always says he can’t even draw stick figures. Here he is drawing with a stick. The page is filled with spirals – they look like electrical coils.

Krista is the LLO helping out and she’s selected a mix of people to join in today.

Lily’s diabetes has cruelly left her an amputee and she rarely leaves her room.

Maggie’s hearing loss isolates her from conversations. While stroking soft feathers and crunching the dried leaves, they share stories of their encounters with magpies.

David doesn’t know what to do with the blank piece of paper in front of him. With gentle direction, the artist is guiding his hand across the page – he chooses black charcoal to make repetitive shapes that mimic the bird’s markings.

Wally is identifying the birds and wildlife he remembers from his childhood and draws the sounds he hears, using an iPad. He finds it easier than gripping a pencil as a recent stroke has impaired his arm movement. Krista sits with him and learns that he used to play the violin – something she can connect with him about.

It’s hard to engage Ivy though. Her dementia is causing agitation and distress and she’s confused by her dead husband’s absence and is struggling to start drawing. With paintbrush in hand, she stops mid-sentence, and closes her eyes. Wait. Is she humming? This music is transporting her to another place and time. It’s reflected on her face and in her change of mood. She returns to her drawing and quietly paints her homeland flower.

You close your eyes too. You take a deep breath and feel the beginnings of a smile. Your day just got better.

This story is fictional but it’s based on actual case studies across various aged care facilities. The names have been changed to respect the privacy of the residents.

How will you or your workplace feel like a year from now if your people were regularly engaged in meaningful activities?